Communication According to Ocean Vuong

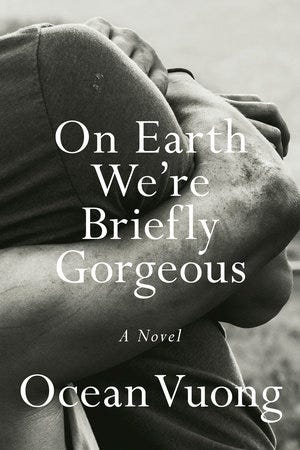

Ocean Vuong's fiction debut, 'On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous,' may well be my book of the 2010s.

On Books…

I own two copies of Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. The first a byproduct of pre-ordering the poet’s fiction debut. The second came to me, as all great things do, in a local book store. I was in Boston. I was with my best friend. We just had breakfast at the store—what an invention, the bookstore cafe—and wandered inside to check out their selections. I saw the Vuong staring at me, with a shiny “Signed” sticker decorating its book jacket. I was sold—what’s wrong with two copies, anyway? Months removed from its June release, and just a month and change into the new decade, I regard On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous as my book of the 2010s.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is a literary masterwork. In terms of structure, the novel is a letter written from main character Little Dog to his mother, who cannot read. Immediately, we’re confronted with the futility of language. We’re confronted with the hard truth words are not enough, yet they are all we have. Vuong forces us to question how we communicate, if communication is even possible. As we read, we realize any and all communication is a privilege.

I found myself in our queer and unheard Little Dog. I found myself in his straining to open himself up to his mother. While my mother is literate classically, she is essentially Donna-illiterate. For so many queer youth in America—the world over, too—I imagine they feel the same way Little Dog feels. I imagine they are struggling to be heard, while doing everything in their power to explain themselves. I imagine the droves of people screaming into a vacuum, and I imagine their relief at seeing themselves so boldly on the page.

Moreover, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous signals Vuong’s poetic ethos. Whole passages of the novel feel like they could easily be slotted into the follow-up to 2016’s Night Sky With Exit Wounds, the poetry book that secured Vuong’s Whiting Award, well-earned acclaim, and my heart. There is a tenderness to Vuong’s prose. It is tactile. Reading Vuong is like taking the hand of your lover, tightly. You feel secure and magnetized. Vuong’s prose is as energetic and dynamic as his poetry. Each word slithers ever so into the next, and before you know it, you’re pages upon pages deep into the devastating story of Little Dog. To read Vuong is to excavate and discover yourself.

All throughout On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, by virtue of its structure, Vuong is in search of something. It would be banal to say he seeks The Truth. There’s a depth here beyond truisms meant to satisfy the self. We recognize Vuong is pining through memory. Each recollection is so rich and thick upon the page. Vuong’s “truth” should be absolute, and yet, every pulpy passage acts as a reminder understanding is not immediately granted. Though we must speak to survive, so much of our lives is dependent upon another’s eyes and ears. As a reader, we feel suddenly helpless. How can it be that only we hear Little Dog? Born of this frustration is the tension and weight of the novel.

How we communicate is crucial to who we are. Our jargon, our cadences, our eclectic mannerisms all sum up to be our personas. According to Ocean Vuong, according to On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, the attempt to communicate is much less than half the battle. When an attempt is made to be heard, we have to put our trust into our listeners. That trust is precious and easily broken. The story of Little Dog is winding and full of heartbreak. We hear him wailing over and over. But his mother, the addressee of Vuong’s stunning letter? She will never have that experience. To be heard is a gift, Vuong implies. Communication, according to Vuong’s work, is a tale of promise, trust, and immense privilege.

This is where I break and say: Many years ago, I met Ocean Vuong at a poetry reading. He hugged me and told me the world needed my voice, and I cried—as I often do. Before penning On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Vuong carried with him the importance of voice and hearing. Vuong heard me without my speaking. We can only hope Little Dog’s mother hears him without reading. We can only hope our queer youth are heard, too. Some people go their entire lives being relegated to a whisper, to a letter. This is the ultimate tragedy of On Earth We’re Breifly Gorgeous.

On Craft…

This week I want to talk about visibility and work ethic. Here’s a question: If a writer is working to the bone, but doesn’t tweet about it, have they actually done any work?

Social media has given us the tools to form communities around our labor. Shouting into the void about your work struggles will usually lend itself to ever-fun commiserating. It feels good to complain with your tribes. Too, when you complain about the work, you’re signaling to the world you are working. Every time I tweet about a piece mocking or taunting me, I’m secretly hoping people remember I’m still here. I still do this. In fact, I would be nothing without this. And yet, I want to tweet less; I want to work more. How to achieve balance?

It’s important to remember Twitter is only as real as it isn’t. If you’re the superstitious type—like me—it’s natural to keep certain things to yourself. The downside here, is that all day you’re flooded with notes from other people: Their work, their success, their failure (which still implies work being done). It can get heavy, feeling like everyone is doing so much while you’re just chugging along. Suddenly, there is a feeling of if you’re not doing the absolute most time can buy, you’re doing nothing.

This binary thinking can sink a writer. The beauty of being a writer and not being an internet personality—though some people will tell you one begets the other—is you get to live in the shadows for as long as you like. Then you emerge with your piece. Finally, you leave the scene. The work is done, and it starts up again. You find your rhythm. You feel good.

The work is about the physical act of the work, not the announcement of the work. Your work ethic has nothing to do with your visibility on socials. Your work ethic is established the moment you build a relationship with the page. The very notion you can measure someone’s worth by how much they produce and announce is a capitalistic trick in itself. The system is broken, and is designed to guilt you into doing more, more, more and faster, faster, faster. The system is designed to make you feel guilty. But all you need to do is spend time with yourself and the writing. Tweet or don’t, but never live by the sword of Twitter itself.

Now, this is where I break and say: Not all visibilities are created equal. For some folx, they have no choice but to be hyper-visible online. It is a privilege to be able to be offline. In my little sphere, I can say women of color frequently—and rightfully—complain about having to be hyper-visible to even get a shot at some of the same opportunities afforded to their less engaged white peers. Without question, this is wrong and emotionally taxing. Again I say: The system is broken. In a perfect world, everything would come down to the page. But that’s not reality. Instead, we need to negotiate our relationships to what extends beyond the page closely.

I’ll leave everyone with this: There is a life beyond the timeline. Don’t forget to live in the realm of the byline when you can.